REMEMBER WHEN . . . Volume 5

ARTICLES FROM DISCOVER THE TREASURES - Volume 5

- BURLINGTON'S CIVIL WAR MONUMENT -

- RELOCATION OF HILLSIDE TAVERN -

- MURPHY PRODUCTS COMPANY -

- IMPROMPTU PARADES -

- EARLY DAYS OF THE AUTOMOBILE IN BURLINGTON

BURLINGTON'S CIVIL WAR MONUMENT

Erected more than 136 years ago on a spot in Burlington Cemetery donated by the Town, Burlington's Civil War Soldiers Monument stands as a tribute to the area's "Boys in Blue" who lost their lives during, or died after, defending the United States against the rebels' attempt to separate the nation. Believed to be the first such memorial in southeastern Wisconsin, the Soldiers Monument, shown in the accompanying photo taken by Tim Beix, was dedicated in 1880.

The idea for the monument was suggested by Burlington attorney Henry Allen Cooper in a Decoration Day speech in 1879. Cooper, who was born in Spring Prairie and grew up in Burlington, went on to serve for 36 years in the U.S. House of Representatives. Following Cooper's 1879 speech, Burlington's veterans appointed John Reynolds (photographer Tim Beix's great grandfather), Edwin R. Smith, and Hiram A. Sheldon as a committee to bring before the citizens for immediate action the subject of a monument to those soldiers whose bodies were never recovered.

About a month later, the Standard reported that it was beyond doubt that a monument would be erected at the cemetery in the near future. The paper said that funds had been, were being, and would be donated to cover the cost of the monument. In September the Burlington Monument Association was organized with Louis Konst, John Reynolds, and Theodore Riel appointed as a committee to receive plans and propositions for a monument.

In November contributors to the monument fund selected a design offered by McDonald and Blakeman of Spring Prairie and voted that the monument be made of the best Sutherland Falls white marble from Vermont. The monument was to be 22 feet high, crowned by an eagle perched on a globe, and was to set on a four-sided pedestal. The contract for constructing the monument was awarded to Burlington marble dealer John B. Klane for the sum of $775.

As Klane was preparing the monument, some residents suggested that the monument be placed on a principal street rather than in the cemetery. Palmer Gardner offered three acres along Randolph Street, with the Standard editor endorsing the plan. Members of the Monument Association, however, by a majority of 25 to 2, voted to place the monument in the cemetery.

As time for the May 31, 1880, dedication neared, it was announced that the flag of the Old First Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, which was carried at the battle of Perryville (Chaplin Hills), Kentucky, would be present at the ceremony. The flag was badly shattered by shot and shell and it was in defending it against the rebel charge that two Burlington men, John Weinborn and Julius Lueck, Jr., together with many others, laid down their lives.

The Decoration Day ceremonies, after being delayed by a morning rain, started about 1 p.m. at Teutonia Hall (corner of what is now Milwaukee Ave. and Kane St.). The procession was led by the Burlington Brass Band, followed by a carriage carrying the chaplain, orators, and president of the day Lewis Royce. Royce's only son, Glaucius, had lost his life at Williamsburg, Virginia. Next came the old soldiers on foot, followed by the crippled soldiers in carriages, then chorus members in omnibuses, friends of the dead soldiers, and the public generally in carriages.

The procession first went to the Catholic cemetery (St. Mary's) where a short ceremony was held and four veterans' graves were decorated – Peter Wackerman, Charles May, Henry Kies, and Confederate draftee Joseph Kies. The procession then headed to the Town cemetery where another short ceremony was held and the graves of six veterans – Martin L. Crane, John Richards, Christian Haas, Charles Neep, Herman Erdmann, and Henry Martensen – were decorated. The gathering then moved to the monument area where the speakers' platform had been set up and the Soldiers Monument was hidden by flags.

Others killed in battle and named on the monument are Henry E. Benson (Bull Run), Glaucius Royce (Williamsburg), Julius Lueck, Jr., and John Weinborn (Chaplin Hills), Dennis Callaghan (Prairie Grove, Ark.), August Schultz and George Martin (Jenkins Ferry, Ark.), and William Madama (Peach Tree Creek, Ga.). Also named on the monument are those who died in hospital or after returning home. They are Julius Landgraff, Gustave Heublein, Joseph Brainard, Martin Luther Crane, Christian J. Haas, Henry Martensen, Charles Neep, Peter Wackerman, Charles May, John C. Richards, Oliver Norris, Herman Erdmann, Herman Wetterroth, and Henry J. Kies (who had died after enlisting but before being mustered in). Additional names – of honorably discharged soldiers – were to put on the monument after their death.

The monument stands on a large artificial mound below the surface of which is a foundation several feet deep. Upon this rests a solid block of limestone about 6 feet square and 2 feet thick supporting the monument. On the west side of the lower base is the "body" of a "field piece" with a pile of three solid shot at each end of it. Above this the legend, TO OUR FALLEN HEROES, stands out in bold relief. Above are two crossed muskets with bayonets fixed, the guns held together with a cartridge belt with cartridge box attached. Just below the arch which forms the upper part of the base is a drawn sabre lying across its scabbard and resting upon them is a soldier's cap. These arms represent the three branches of the service – the Artillery, the Infantry, and the Cavalry.

At the conclusion of the dedication ceremonies, the veterans returned to Teutonia Hall, where they gave a vote of thanks to the various participants and then broke ranks in regulation manner.

RELOCATION OF HILLSIDE TAVERN

The moving of buildings in Burlington has a long history. All types of buildings, from small to large – including barns, garages, houses, shops, and commercial buildings – have been moved from one site to another over the years. Many will remember the brick Waller house being moved in 1996 from the Kane Street property of Our Savior Lutheran Church to Pickett Court in the Shiloh Hills subdivision. Some may also remember the 1986 move of the small 1840 brick school building, now called Whitman School, from behind the Roman Uhen house on Madison Street (between Dodge and Pine streets) to Schmaling Park on Beloit Street.

The moving of buildings in Burlington has a long history. All types of buildings, from small to large – including barns, garages, houses, shops, and commercial buildings – have been moved from one site to another over the years. Many will remember the brick Waller house being moved in 1996 from the Kane Street property of Our Savior Lutheran Church to Pickett Court in the Shiloh Hills subdivision. Some may also remember the 1986 move of the small 1840 brick school building, now called Whitman School, from behind the Roman Uhen house on Madison Street (between Dodge and Pine streets) to Schmaling Park on Beloit Street.

The earliest newspaper record the Historical Society has found of a building being moved in Burlington was in October 1860 when the Burlington Gazette reported that wagon maker John W. Edmonds had moved a wooden building, which he intended to use as a carriage factory, to a lot on Pine Street between Sawyer & Barnes Plow Factory and Richard Weygand's Paint Shop.

One of the biggest moving jobs done in Burlington was in April 1909 when a large brick building, known as Veteran Saloon, was moved from the corner of Chestnut and Pine streets, where May's Insurance building now stands, to the property across the railroad tracks on Chestnut Street, where the Charcoal Grill now stands. After the move, the former saloon building housed a feed company, a can factory's machine shop, a freight warehouse, and, in its last years, the Hi-Liter Graphics company. The building was razed in 2001 as part of the City's riverfront development project.

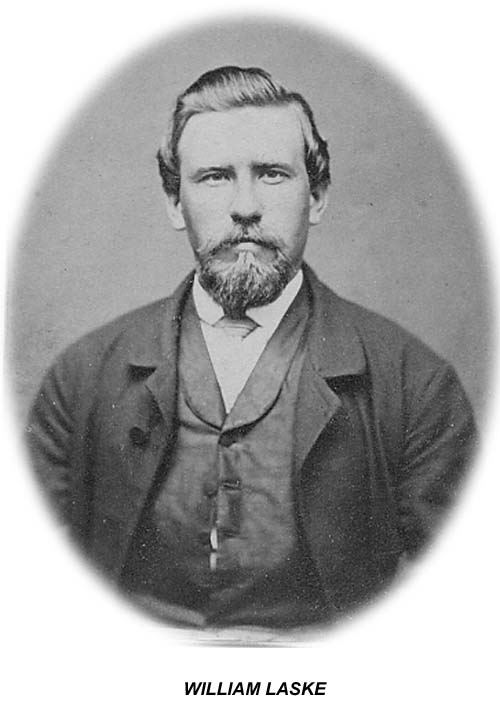

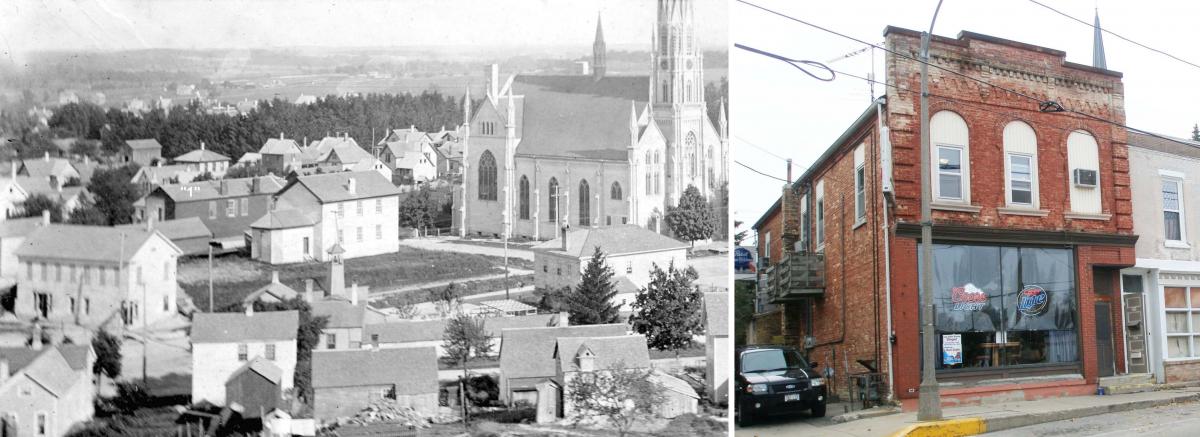

One of the most unusual building moves occurred in 1898 when the long, narrow dark-brick building marked "1" in the black and white circa 1898 photo above was turned around and moved from its location facing Liberty Street (now called State Street) to a location on Jefferson Street where today it is known as the Log Cabin Tavern. The red brick tavern building at 233 W. Jefferson Street is shown in a recent photo above.

The building was moved by a Milwaukee firm for Burlington saloon keeper William Colburn. Colburn had been operating a Hillside saloon on Jefferson Street in a nearby building he leased from Jacob Brehm. When Brehm sold the building and the property it was on in March 1898 to Joseph A. Rueter, Colburn decided to buy the 22-by-60-foot red brick building facing St. Mary's Catholic Church and the 50-by-135-foot lot it was on from Bernhard Ebbers. Ebbers and others had operated stores on the building's first floor while the upper floor was used as a residence.

Colburn paid $2,400 for the Ebbers property which stretched from Liberty Street to Jefferson Street. On June 6, 1898, the Standard Democrat reported that the Milwaukee contractor, with his force of men, had raised the Colburn building, moved it out into the street, turned it around, and had it started for its new location on Jefferson Street, where Colburn had the foundation all ready for the building. After the building was situated on Jefferson Street, Colburn moved his saloon into it on July 1, 1898.

After William Colburn's death in 1905, his sons, Howard and Clarence, operated the saloon. In 1911 the Colburn brothers remodeled the interior using tamarack logs and on St. Patrick's Day, March 17, re-opened the saloon as the "Log Cabin Inn." The Colburn family operated the business until 1927 when it was sold to Michael Fleuker. Subsequent operators have included Harry and Margaret Reynolds, Warren and Irene Milatz, Sharlene Jacobs, and Charles and Karen Dexter.

MURPHY PRODUCTS COMPANY

Burlington has been home to many industrial firms over the years. Some of the larger ones – such as the Wisconsin Condensed Milk Company (later called Nestles Milk Products, Inc.), Burlington Blanket Company (later called Burlington Mills), and Burlington Brass Works – started in the late 1800s or early 1900s, lasted for 50 years or more, and provided stable employment for Burlington area residents and some newcomers over those many years.

Another large industry – Murphy Products Company – did not move to Burlington until the mid-1920s, but it also lasted a long time and provided stable employment for many residents and newcomers. As a former Walworth County agricultural agent and manager of a Delavan-area farm, James H. Murphy studied problems farmers were having with their beef and dairy cattle and created combinations of protein, vitamins, and minerals that could be used to supplement homegrown livestock feeds. Joined by his brother, Lawrence, the two Murphys started a company producing mineral concentrates in Delavan in 1921.

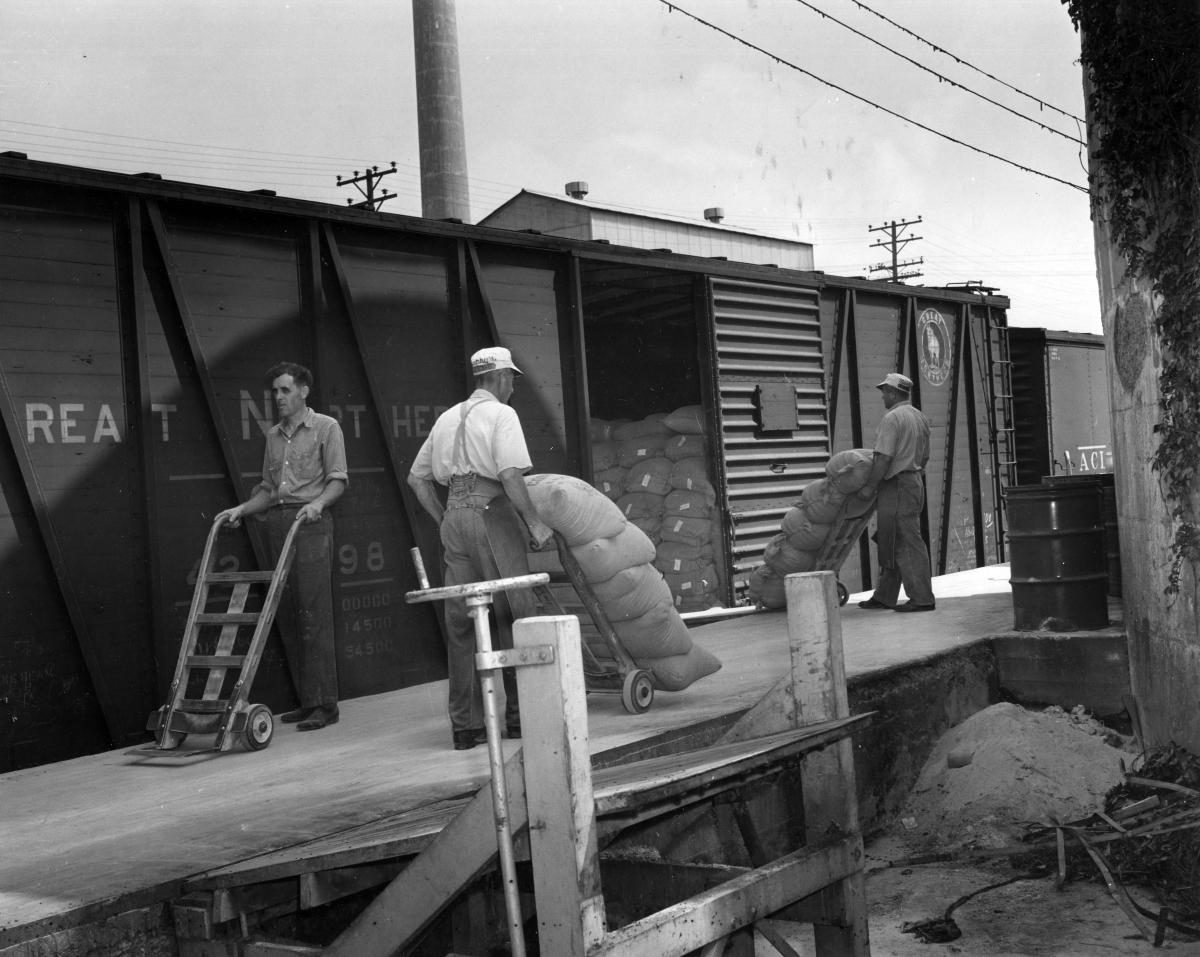

The business grew and, in 1925, the Murphys moved the company to Burlington, where it occupied a vacant milk plant on Dodge Street. As time went on, the firm expanded its facilities and added product lines for hogs, sheep, chickens, and other animals. Eventually, a complete line of Murphy Cut-Cost Concentrates for all classes of livestock and a complete line of starter feeds had been developed. The products were sold primarily throughout the Midwest. On Christmas Eve 1951, disaster struck the company as a fire destroyed the manufacturing plant and a part of the warehouse facilities. (Aftermath of fire shown in photo at right.) Using borrowed equipment, milling resumed at an Illinois location until a new automated plant was opened in Burlington. In the 1960s, the company grew, establishing plants in North Carolina, Mississippi, Texas, and California. The company was sold to the Schlitz Brewing Co. in 1971 and changed hands a few times thereafter. The original building and plant were razed in 2013.

On Christmas Eve 1951, disaster struck the company as a fire destroyed the manufacturing plant and a part of the warehouse facilities. (Aftermath of fire shown in photo at right.) Using borrowed equipment, milling resumed at an Illinois location until a new automated plant was opened in Burlington. In the 1960s, the company grew, establishing plants in North Carolina, Mississippi, Texas, and California. The company was sold to the Schlitz Brewing Co. in 1971 and changed hands a few times thereafter. The original building and plant were razed in 2013.

The accompanying photos show some of the facilities and operations of Murphy Products Company. The photos are a part of the company's archives donated to the Burlington Historical Society by Robert R. Spitzer, who joined the firm in 1947 and succeeded James Murphy as the firm's head in 1958.

IMPROMPTU PARADES

Over the years, Burlington has had a considerable number of well-organized and pre-planned parades marking or celebrating such events as ChocolateFest, July 4th, Memorial Day, Veterans Day, May Day-U.S. Way, Burlington’s 1935 Centennial, the 1876 U.S. Centennial, and the 1976 U.S. Bicentennial. There have also been numerous Christmas and Halloween parades, doll buggy and bicycle parades, and high school homecoming parades.

But sometimes the parades don’t happen often enough or at the right time for those who “love a parade.” When that occurs, some will gather their friends and neighbors and put together their own parade. The following photos show three impromptu parades that have occurred in Burlington over the years and that attracted the eye of alert photographers.

Paradin’ around the neighborhood in July 1951, under the watchful eyes of several observers, were members of the younger set of Schemmer Street. Included in the group, shown in this Free Press photo, were Dave Ebbers, Harold Welch, Barbara Ebbers, Mary Pat Ebbers, Dickie Schneider, Kay Leemkuil, Jimmy Schneider, Kenny Schneider, Dickie Ebbers, and Norbert Rausch. The parade route proceeded along Schemmer Street to Geneva (now W. State) Street, along Liberty Street (also now W. State Street) to McHenry Street, and back to Schemmer Street, where refreshments and a party awaited.

Paradin’ around the neighborhood in July 1951, under the watchful eyes of several observers, were members of the younger set of Schemmer Street. Included in the group, shown in this Free Press photo, were Dave Ebbers, Harold Welch, Barbara Ebbers, Mary Pat Ebbers, Dickie Schneider, Kay Leemkuil, Jimmy Schneider, Kenny Schneider, Dickie Ebbers, and Norbert Rausch. The parade route proceeded along Schemmer Street to Geneva (now W. State) Street, along Liberty Street (also now W. State Street) to McHenry Street, and back to Schemmer Street, where refreshments and a party awaited.

For a time after Burlington’s firemen decided in 1922 that they would not undertake their customary Fourth of July celebration, it looked as though the nation’s birthday would pass unobserved in the City. This did not suit the Burlington businessmen’s club, which stepped in to finance a celebration that included baseball games, a mammoth fireworks display, and a comic circus parade. The parade started near the Soo Line depot on Pine Street, wound through the downtown streets, and ended up at Athletic Park (now Beaumont Field). What the parade lacked in length was more than made up by the originality of the participants. In this photo, provided courtesy of the Racine Heritage Museum, some of the “well-dressed” participants pass by the Crystal (later State) Theatre near the Pine Street intersection with Geneva and Short streets (now Milwaukee Avenue). The tracks running along the bricked Geneva Street are those of the Interurban electric line which operated between Burlington and St. Martins from 1909 until 1938.

For a time after Burlington’s firemen decided in 1922 that they would not undertake their customary Fourth of July celebration, it looked as though the nation’s birthday would pass unobserved in the City. This did not suit the Burlington businessmen’s club, which stepped in to finance a celebration that included baseball games, a mammoth fireworks display, and a comic circus parade. The parade started near the Soo Line depot on Pine Street, wound through the downtown streets, and ended up at Athletic Park (now Beaumont Field). What the parade lacked in length was more than made up by the originality of the participants. In this photo, provided courtesy of the Racine Heritage Museum, some of the “well-dressed” participants pass by the Crystal (later State) Theatre near the Pine Street intersection with Geneva and Short streets (now Milwaukee Avenue). The tracks running along the bricked Geneva Street are those of the Interurban electric line which operated between Burlington and St. Martins from 1909 until 1938.

With large parades already held in the City for Memorial Day and the Alice in Dairyland competition during the previous two months of 1968, Burlington did not hold a Fourth of July parade that year. Nevertheless, as shown in this photo by Emmett Raettig, a patriotic group of youngsters in the Perkins Boulevard and Edward Street area observed the Fourth with a parade, complete with clowns, flags, floats, and a band. Even though it rained during the parade, the participants’ spirits were not dampened. The parade, organized by Ron Thate, was the third he had organized in as many years. The paraders in the photo are proceeding east on Chandler Boulevard toward the intersection with Edward Street.

With large parades already held in the City for Memorial Day and the Alice in Dairyland competition during the previous two months of 1968, Burlington did not hold a Fourth of July parade that year. Nevertheless, as shown in this photo by Emmett Raettig, a patriotic group of youngsters in the Perkins Boulevard and Edward Street area observed the Fourth with a parade, complete with clowns, flags, floats, and a band. Even though it rained during the parade, the participants’ spirits were not dampened. The parade, organized by Ron Thate, was the third he had organized in as many years. The paraders in the photo are proceeding east on Chandler Boulevard toward the intersection with Edward Street.

EARLY DAYS OF THE AUTOMOBILE IN BURLINGTON

This article is adapted from a paper presented by Burlington native, Newton Bottomley, to the Burlington Historical Society in September 1939. At that time, Burlington stores opened on Saturday evenings to accommodate both city and, especially, farm families whose weekdays were taken up by work and by family, school, and community activities. At that time, many families had only one automobile.

When you drive to town on Saturday evening and have difficulty in finding a place to park your car, it is hard to realize that 35 years ago – 1904 – Burlington boasted but two or three "Horseless Carriages," and the purchase of one was headline news. I am told the "steamer" owned by Leonard Smith, which he bought in 1902, was the first automobile owned in Burlington. Patterned after the horse-drawn buggy, with the steering wheel on the right hand side, there were as many different designs and auto makers as there were cars. Some had steering wheels, while others had tiller steering. Some had regular buggy wheels, with solid rubber tires, while others had smaller diameter wheels with pneumatic tires. These pneumatic tires were usually guaranteed for 1,000 miles.

The maximum speed of these early cars was from 10 to 15 miles per hour. Dirt streets and roads, whose condition changed with the weather, were the norm. Hard surfaced (brick) streets began to be installed in Burlington in 1909. It was not until 1919 that Racine County voted to issue bonds to build 125 miles of hard roads, including 2 miles from Burlington to Brown's Lake.

Due to the horses being frightened upon meeting one of those early "road demons," the cars were very unpopular. In January 1905, for example, 3,000 farmers in Racine, Kenosha, and Walworth counties petitioned the Wisconsin legislature for a law to protect farmers against automobiles and their drivers.

On July 1, 1905 – when fewer than a dozen Burlington people had cars – the Wisconsin law went into effect requiring registration of all motor vehicles, and the carrying of a proper certificate and number plate, marked with the official "W." It also required that autos must have at least one reasonably bright light pointing forward, from one hour after sunset to one hour before sunrise. All auto drivers were required to stop their machines whenever a signal was given by the driver of a horse-drawn vehicle.

The license referred to cost one dollar for the registration and plate, and was good during the life of the vehicle. The plate furnished by the state consisted of thin aluminum numbers three inches high, riveted to a sheet of zinc about 1/16th inch thick and only one plate was required. In 1907 the law was changed to require yearly registration. Two plates were furnished, and the price was raised to $2.00. Two years later the license fee was changed to $5.00, and in 1917 the $10.00 and up schedule, depending on the weight of the car, went into effect.

Lights and horns were not furnished with the early autos when you bought them. They had to be bought extra. Bumpers were unknown. Tops were extra. Windshields were unknown. Some cars offered a choice of wire wheels or wood wheels which were known as "artillery" wheels. When you had a flat, the tire was pried off the rim, repaired, put back, and pumped up with a hand pump. Gasoline was purchased at the grocery or hardware store for some eight or nine cents per gallon, and poured into the gas tank by means of a funnel with a screen or chamois strainer to keep out water and dirt.

Engines in these early models were mostly one or two cylinder, with dry batteries and a vibrating coil to produce the spark. The engines were located either in the rear or under the middle of the car. The front of the car was the place for the radiator. One of the early models had a step at the rear for entering through a swinging section of the back seat. It had the engine under the center of the car, and was cranked for starting from the side. Mechanical repair on the engine was pretty much from underneath the car, which probably inspired that song about "he had to get under, get out and get under to fix up his automobile."

As late as 1917 the laws provided that no person could operate or drive any automobile, motorcycle or other similar vehicle along any public highway, within the corporate limits of any city or village, at a speed exceeding 15 miles an hour, nor outside the corporate limits at a speed exceeding 25 miles an hour. The speed limit through any cemetery, or any county or state hospital or poor farm grounds was 8 miles an hour. In turning corners, in going around curves, at sharp declines, at the intersection of any street or crossroad, and where for any cause the view in the direction in which the vehicle was proceeding was obstructed, the speed was to be reduced to such rate as would tend to avoid danger of accident.

Motor vehicles were also required to be provided with efficient brakes, adequate bell or horn, and muffler. The use of sirens was limited to police, fire department vehicles, and hospital ambulances. The unnecessary use of a horn, or driving with the muffler open in a city or village, was prohibited.

On June 28, 1919, the Racine paper reported that the city council was to meet to raise that city's speed limit for automobiles from 12 to 15 miles per hour.

By 1925 Wisconsin's speed limits had been increased to 30 miles per hour for country driving, with 15 miles in cities and villages, and 12 in cemeteries, parks, county or state hospitals, or poor farms, or passing school grounds.

In conclusion, Bottomley said that it was anybody’s guess what the future laws would provide, but that the increase in accidents and deaths had come as the power and speed of the auto had been increased.

Early automobiles, as well as horse-drawn conveyances, are seen on Pine Street in this circa 1906 photo from the collection of the late Jane Wagner Hoganson. The large building with the sidewalk canopy was the Hotel Burlington, later the site of such businesses as the Plush Horse, Charley Brown's, Sharkey's Lounge, and the Sci-Fi Cafe. The building to its right, with the second floor "bump out," was the agricultural implement store of Mrs. Hoganson's maternal grandparents, the Bankes family. Later occupants included Reineman Hardware, Bulletin Printing and Office Supplies, and now Burlington Flowers and Interiors. Joe's Place, to the left of the hotel building, was the tavern of Joseph Rittman. The building, later occupied by, among others, Luhn and Runzler's and Caesar and Jim's taverns, is now the site of John's Main Event. Store buildings at the far left include the Reineman Hardware Co.'s original site and the agricultural implement business of Herman Dettman and Robert Hoff.